Josef Scharl: Letter to Heinrich (or Ulrich) Lechleitner (2 March 1939)

A quarter of a year after he migrated to the USA, painter Josef Scharl got in touch with a friend in Munich. The tone of the letter, a “sign of life”, is joyful and optimistic. After experiencing years of distress under the Nazis, everything now seemed to point to a fulfilling creative period in exile.

Josef Scharl: Letter to Ulrich Lechleitner (25 December 1939)

In late 1939 Josef Scharl, living in New York without his family, sent a letter to Munich. His first year in exile was drawing to a close. The recipient of these lines, Scharl’s friend Ulrich Lechleitner, had recently married. Along with New Year’s greetings, Scharl extended his congratulations on the marriage.

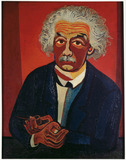

Josef Scharl: Portrait of Albert Einstein, painting (1944)

The Nobel laureate Albert Einstein and the painter Josef Scharl first met in Berlin in the 1920s. A decade later, scientists and artists were no longer welcome in Germany in the worldview of the Nazis.

Josef Scharl: The massacre of the innocents, painting (1942)

Josef Scharl emerged from the First World War with traumatic memories. The collapse of a trench had left the painter’s right hand paralysed. It was only in the last year of the war that he finally managed to get it treated.

Joseph Hahn: In Memoriam Franz Peter Kien, typescript (1991)

The artist and writer Joseph Hahn dealt critically in his work with social problems and historical events. One aspect he looked at closely throughout his entire work was the Holocaust.

Joseph Hahn: Zum Gedenken an den großen, jungen Franz Peter Kien (In memory of the great, young Franz Peter Kein, 1953)

Remembering a dead artist and friendJoseph Hahn had spent seven years in exile in America when he presented his first works in an exhibition. His first solo exhibition followed just one year later (1953).

Joseph Hahn: Zum Gedenken an meine Eltern, (In memory of my parents), manuscript (2004)

In 1939 Joseph Hahn lost his homeland in a very literal sense; the Sudetenland no longer existed by fact of its occupation. But it was not just the country that he had lost.

Joseph Roth in the Parisian Café Le Tournon (circa 1938)

When the Nazis came to power, Joseph Roth went into exile in Paris, living initially in the Hôtel Foyot, where he had also stayed during previous trips to Paris. After having to watch his domicile be torn down, the Hôtel de la Poste and the Café Le Tournon, which was part of the hotel, became his new place of refuge and where he did his writing.

Joseph Roth: Beichte eines Mörders. Erzählt in einer Nacht, manuscript (1936) [Confession of a Murderer. Told in One Night. (published in English in 1937)]

Joseph Roth had been working on his novel Confession of a Murderer since 1935. The first chapter appeared with the title Der Stammgast as an advance release in Das neue Tagebuch and was then published by the Amsterdam publishing house de Lange in 1936.

Joseph Roth: Das Haus des Herrn Kristianpoller, manuscript (presumably 1934)

Unpublished preliminary work for Tarabas (1934)In only one sentence Joseph Roth draws his readers right into the heart of the East-Galician environment in which his main character Joel Kristianpoller lives, a wealthy Jew from Brody, where the story takes place and which was also Roth’s birthplace and a city with a long Jewish tradition. The occurrence he describes here plays a key role in the novel Tarabas.