Press ban

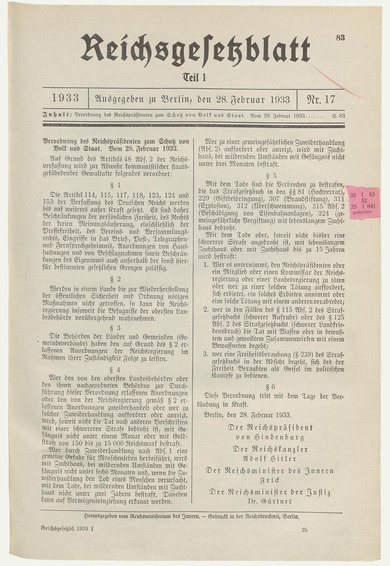

Censorship, that is, the control of information that is to be passed on in either written or spoken form, is an instrument used often in totalitarian states to prevent the dissemination of undesired information. The Nazis also undertook measures to consolidate their power and gain control over all areas of public and private life. The Reichstag Fire Decree from 28 February 1933 already placed limitations on the right of people to express their opinion freely. Freedom of the press and the freedom of association and assembly were also restricted, state interference in the privacy of postal correspondence, telegraphs and telephone calls was permitted, house searches and confiscations were legalised.

The press, mainly newspapers and magazines, the most popular media of the times, but also radio and film, were censored to get rid of oppositional or critical contents and were to serve as the mouthpiece of the new regime in future. The Reich Ministry of Propaganda, which was headed by Joseph Goebbels was in control of monitoring these processes.

One of the first acts was to seize and ban the party newspapers of the SPD (social democrats) and the KPD (communists). Journalists who expressed criticism of the regime were gotten rid of by introducing obligatory membership of the Reich Press Chamber, which operated under the auspices of the Reich Chamber of Culture. Anyone seen to be politically untrustworthy was not accepted as a member, which amounted to a professional ban.

As an additional measure to control the newspaper publishers, the “Schriftleitergesetz” (Editor Law) was passed in October 1933 and came into force on 1 January 1934. By installing editors-in-chief who were close to the NSDAP – the so-called “Hauptschriftleitern” (Main Editors), who were bound to follow the instructions by the Reich Press Chamber and the Propaganda Ministry, editors and publishers were stripped of their control over their own print media. What is more, Jewish journalists were only allowed from now on to work for the Jewish press.

The policy of bringing organisations into line with Nazi doctrine meant the end of diversity of opinion in the German press. The percentage of newspapers owned by the NSDAP rose to 82.5% by 1944. Robbed of any opportunity to work, many journalists left the country, while others accepted censorship of their work in order to keep their jobs.

Weiterführende Literatur:

Werner Fuld: Das Buch der verbotenen Bücher: Universalgeschichte des Verfolgten und Verfemten von der Antike bis heute. Berlin: Galiani 2913

Wolfgang Benz (Hg.): Handbuch des Antisemitismus. Judenfeindschaft in Geschichte und Gegenwart. Band 4: Ereignisse, Dekrete, Kontroversen. Berlin u.a.: De Gruyter Saur 2011