Passport

Der Paß ist der edelste Teil von einem Menschen. Er kommt auch nicht auf so einfache Weise zustand wie ein Mensch. Ein Mensch kann überall zustande kommen, auf die leichtsinnigste Art und ohne gescheiten Grund, aber ein Paß niemals. Dafür wird er auch anerkannt, wenn er gut ist, während ein Mensch so gut sein kann und doch nicht anerkannt wird.

[A passport is the most precious part of a person. It isn't as easy to make as a human being. A person can be made anywhere, in the giddiest of circumstances and without reason, but that is never the case with a passport. It is regarded as valid if it is good, while a person can be good and yet not be regarded as valid. (ed. trans.)]

Bertolt Brecht, Flüchtlingsgespräche, 1940/41

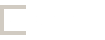

A passport is an official document which determines with certainty the identity, nationality and place of residence of a person. As an identity document it determines who is entitled to live where, when and for how long, and who may enter and leave. As an instrument of control, a passport is checked at state borders, for example. A person with no identification papers, or the wrong ones, will face rejection or discrimination. Sometimes this results in an illegal border crossing.

The rights which derive from holding a valid passport are taken for granted by many people. However, forcible expulsions, wars, forced escape or expatriation result time and again in situations in which people are incapacitated by the loss of valid papers. The presence or absence of a passport and identity documents therefore determines the everyday life of refugees and immigrants in a special way: questions regarding transit visas, exit, entry or residence permits are commonplace for people who are fleeing or in exile. Some refugees obtain fake documents.

During the Nazi period from 1933 to 1945, not having valid papers or losing identification documents brought about hitherto unprecedented consequences, including deportation. Many refugees and victims of persecution lost not only all civil rights, but also their possessions: they were penniless and stateless - searching for ways to be accepted in another country. The publication of expatriation lists in newspapers was an additional form of exclusion and exposure. The stamped letter 'J' or the mandatory first names 'Israel' and 'Sarah' in German passports marked the passport holder as a Jew, thus making them more identifiable. In this way passports became part of the anti-Semitic measures of the Nazi regime.

Many exiles have addressed the topic of citizenship, and the question of valid documents in autobiographical and literary texts. For example, Bertolt Brecht in his Flüchtlingsgesprächen, Anna Seghers in Transit or Franz Werfel in Jacobowsky und der Oberst.

Even today, passports play an important role in connection with flight and migration: in the status and rights of refugees without identity papers, for example, or the question of whether a person should be allowed to have more than two passports.

Further reading:

Thomas Claes: Passkontrolle! Ein kritische Geschichte des sich Ausweisens und Erkanntwerdens, Berlin 2010

Valentin Groebner: Der Schein der Person. Bescheinigung und Evidenz. In: Hans Belting, Dietmar Kamper und Martin Schulz (Hg.): Quel corps? Eine Frage der Repräsentation. München: Fink 2002, S. 309-323.

Payne, Charlton: „Der Pass zwischen Dingwanderung und Identitätsübertragung in Remarques Die Nacht von Lissabon.“ In: Dinge des Exils. Jahrbuch für Exilforschung. (31), München 2013, S. 343-354.