Denaturalisation

Denaturalisation

A person becomes a citizen of a state either by origin or through a bureaucratic naturalisation procedure. A citizen is typically endowed with certain rights, such as the right to vote and the right of abode. If a person is “denaturalised”, he/she loses these rights together with his/her citizenship and may be expatriated.

In Germany, full civil rights were first extended to all residents in 1919. The Nazis created the option of using denaturalisation for their purposes in their first year in government in 1933. The “Law on the Revocation of Naturalization and the Deprivation of German Citizenship” of 14 July 1933 empowered the authorities to denaturalise naturalised Jewish immigrants who had come from the east following the November revolution of 1918. It also denaturalised opposition politicians and artists who were already in exile abroad and led to the confiscation of any remaining assets in Germany.

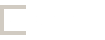

Publication was carried out through lists of people in the “Deutscher Reichsanzeiger”. By the end of the Second World War, a total of 39,006 Germans had been denaturalised in 359 lists.

In the first years of the Nazi dictatorship, denaturalisation was primarily an instrument of persecution of political opponents. In the later expulsion, persecution and murder of the European Jews, the withdrawal of citizenship was used as a means of enrichment by stealing the deported people's assets. The “Eleventh Decree to the Reich Citizenship Law” of 25 July 1941 stipulated that Jewish Germans would lose their citizenship automatically if they crossed the German border during their deportation and any assets left behind would be automatically confiscated by the state.

After 1945, people who were critical of the government were also denaturalised by the GDR. One prominent case of this was the singer-songwriter Wolf Biermann in 1976. Protests by artist colleagues led to further denaturalisations. Incarcerated political prisoners were also forced to apply for their own denaturalisations.

As a rule, these expatriated East Germans were accepted by the Federal Republic of Germany, in which denaturalisation had been prohibited since the introduction of the Basic Law in 1949.

At present, citizenship of a state is not always unambiguous. In Germany, for instance, the citizenship law also provides for dual citizenship.

Today, many refugees still become stateless when they flee a state and are obliged to seek refuge in a receiving state.

Further reading:

Robert Grünbaum: Wolf Biermann 1976: die Ausbürgerung und ihre Folgen. 2., überarb. Aufl. Erfurt: Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Thüringen, 2011 Alexander Stephan: Überwacht. Ausgebürgert. Exiliert. Schriftsteller und der Staat. Bielefeld: Aisthesis-Verlag 2007

Michael Hepp (Hg.): Die Ausbürgerung deutscher Staatsangehöriger 1933-1945 nach den im „Reichsanzeiger“ veröffentlichten Listen. Saur Verlag, München 1985 (3 Bände)