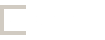

Max Beckmann

Max Beckmann

Die Rolle die Du zur Zeit spielst ist die schwierigste aber auch großartigste die Dir das Leben bieten konnte – vergiß das nicht – Max Beckmann – und gerade so wie sie ist.

[The role you yourself are playing at the present time is the most difficult, but also the greatest one life could offer you – don’t forget that – Max Beckmann – and I mean the role exactly as it is. (ed. trans.)]

Max Beckmann, Diary, 18 December 1940

| Born | on 12 February 1884 in Leipzig, Germany |

|---|---|

| Died | on 27 December 1950 in New York, United States of America |

| Exile | Netherlands, France |

| Profession | Painter |

The ten years that the painter spent mainly in Amsterdam make up a separate, important era in his life and creativity. Immediately before this, there were five years in Berlin. They followed the Frankfurt years from 1916 to 1932, which ended for Beckmann with the bitter experience of his ostracism as a “degenerate” artist and his dismissal from his teaching post. After his time in Holland, he had his first stay in America in 1947/1948, and soon moved permanently to New York.

Even before they assumed power, Max Beckmann had been subjected to attacks from the Nazis, attacks that further increased after 30 January 1933. A letter on 31 March of this year dismissed him from his post as a teacher at the School of Art in Frankfurt upon Main, effective from 15 April. Moving soon afterwards to Berlin, while the artist did have an exhibition in the Kunstverein in Hamburg from 5 February to 5 March, Herbert Kunze from the Museum in Erfurt did not dare show the exhibition there, though it had already been accepted. On 1 July, Ludwig Justi was ‘put on leave’ as Director of the National Gallery, and shortly afterwards the Beckmann Hall of the Kronprinzenpalais that he had arranged was emptied.

In February 1935, the Gestapo seized 81 works by various painters and sculptors at the Hugo Perls auction house in Berlin as “degenerate art” and transferred them to the National Gallery. A number of them were selected as “historically valuable”, and the rest were burned on 20 May 1936 in the boiler room of the Kronprinzenpalais. On 29 March 1936, Reichstag elections were held in which Hitler’s policies were approved by a majority of 99%. On 27 November, on the orders of Goebbels, Reichsminister of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda, the art criticism that had been customary up to then was replaced by the “art report”, because it almost exclusively dealt with acceptable artists and their works, which were not to be criticised.

In April, Beckmann’s wife Mathilde, known as Quappi, went to her sister Hedda in Holland, and Beckmann wrote to her on 28 April, even though he was still thinking about his options in Germany: “And don’t forget to discuss the possibility of emigration with your people. There’s no knowing what else is going to happen. – However, we still have to keep our operations in Berlin going.” Evidently he also enquired about other options in England in August 1936, when the Olympic Games were being held in Germany, while he was visiting his emigrated friends from Frankfurt, Heinrich and Irma Simon, in Dunskaith, Surrey. In February 1937, his last hopes of a life in Germany had clearly faded, as he wrote to Hanns Swarzenski in Princeton on the 15th of the month: “We’re continually poring over plans, and the decision is difficult, but it’s definitely coming soon. The idea with Barr is not bad and might convince me to take your advice, if B. really does get involved.” This refers to an invitation from Alfred H. Barr, Director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and to the idea of emigrating to the USA.

On 18 July 1937, Hitler opened the “Great German Art Exhibition” in the just completed “House of German Art” in Munich. Max Beckmann and his wife Quappi had already emigrated a day earlier, as the artist himself notes in his painting list, underlined many times: “Amsterdam 1937/from 17 July” and beside this later on: “Emigré”

In spite of all the difficulties, the work created in Amsterdam is rich in every sense, not merely as regards its scope, but also its rank: a number of the triptychs, the illustrations to the “Apocalypse” and “Faust”, and many other works. In spite of his exile, Max Beckmann was able, as the Old Masters and only very few artists in the 20th century were, to perceive the richness of life, and to make it his own and formulate it intellectually and sensually. (all quotations ed. trans.)

Further reading:

Beckmann & Amerika. Ausstellungskatalog Frankfurt am Main. Herausgegeben von Jutta Schütt. Mit Beiträgen von David Anfam, Karoline Feulner, Ursula Harter, Lynette Roth, Stefana Sabin, Jutta Schütt und Christiane Zeiller. Ostfildern 2011

Lackner, Stephan: Ich erinnere mich gut an Max Beckmann. Mainz 1967

Lackner, Stephan: Exil in Amsterdam und Paris. In: Ausstellungskatalog Max Beckmann. Retrospektive. Hg. von Carla Schulz-Hoffmann und Judith C. Weiss. München u. a. 1984, S. 147 – 158

Max Beckmann. Exil in Amsterdam. Ausstellungskatalog Amsterdam und München 2007 / 2008. Herausgegeben von der Pinakothek der Moderne. Mit Beiträgen von Carla Schulz-Hoffmann, Christian Lenz und Beatrice von Bormann. Ostfildern 2007

Selz, Peter: Die Jahre in Amerika. In: Ausstellungskatalog Max Beckmann. Retrospektive (s. o.), S. 159 – 172