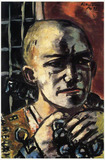

Max Beckmann: Illustrations for Apokalypse (1941-1942)

Max Beckmann: Illustrations for Apokalypse (1941-1942)

“Worked on Appo. Dark Sunday.” This is the entry for 14 December 1941 in Beckmann’s diary. The years 1941 and 1942 are also the years of the illustrations to the “Apocalypse”, now under German occupation in Holland. Max Beckmann received this commission, which provided him with moral and financial support as a “degenerate” ostracised artist and emigrant, but which was also a great artistic challenge, from his close acquaintance in Frankfurt upon Main, Georg Hartmann, the owner of the Bauer Type Foundry. Of course, both sponsor and artist were conscious of the reference to their own period, as expressly stated in the imprint: “In the fourth year of the Second World War, this print was created as the story of the apocalyptic seer became a gruesome reality.” However, Max Beckmann did not see it as his task to update all the visions. This is already evident in the text of the title image, in which two different quotations are combined: “In the beginning was the Word” (Gospel of John 1:1) and “Blessed are the dead who die in the Lord from now on […] for their works follow with them” (Revelation to John 14:13). Of course, the “works” are also the works of art that Max Beckmann had created.

The print run only came to 24 copies, because anything in excess of this would have had to be submitted to the censor. Beckmann produced lithographs on transfer paper in Amsterdam, and these were printed in Frankfurt. In a number of folders, the lithographs were coloured, a small number by the artist himself. Acting as couriers between Amsterdam and Frankfurt were Peter Beckmann, Erhard Göpel and Lilly von Schnitzler.

Thus, the illustrations to the Apocalypse imposed very high demands in many different ways. However, the text of the Apocalypse must also have struck a chord with Max Beckmann in another way. What John sees are visions that represent revelations. If Beckmann already saw an analogy with his own artistry in this, then also in the fact that the images of the Revelation are to be understood symbolically. Nonetheless, the Apocalypse is founded on events of the day, namely the punishment of the Romans as enemies of the Christian community and the promise of final salvation. Did Beckmann also know this; did he see an analogy with the Nazis and those persecuted by them? In any case, the images show that he ‘echoed’ himself a number of times. He himself is John, who is shown “a new heaven and a new earth” in the end; but he is also the sufferer for whom “God will wipe away all tears”, and the one to whom the crown of life is promised if he is “faithful to death”.

Further reading:

Lenz, Christian: Schön und schrecklich wie das Leben. Die Kunst Max Beckmanns 1937 bis 1945. In: Max Beckmann. Exil in Amsterdam. Ausstellungskatalog. Amsterdam / München: Hatje Canz 2007/2008, S. 33-107