Klaus Mann: Diary Entries from 5 June 1940 to 11 December 1942

Klaus Mann: Diary Entries from 5 June 1940 to 11 December 1942

Übrigens sind diese geringen Notizen ja das einzige, was ich in meiner Sprache noch schreibe – ausser [sic!] ein paar Briefen.

[Incidentally, these short notes are the only thing that I still write in my own language – with the exception of a few letters (ed. trans).]

Klaus Mann, Diary from 19 September 1940

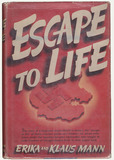

In September 1938, Klaus Mann left Europe permanently and travelled by ship to New York, where he began his period of exile in America. In the USA the author underwent a linguistic transformation as he increasingly drifted away from his native tongue toward English. His very first English-language manuscript, entitled Distinguished Visitors, was never published during his lifetime. From January 1941 to February 1942, Mann published the literary journal Decision. In 1942, the newly-established New York publishing house L. B. Fischer printed his English-language autobiography The Turning Point. That same year, Mann began writing his diary entries in his newly adopted tongue. The shift was abrupt and can be dated exactly to 19 March 1942. The diaries do not, however, reveal a motive for this change in language.

Susanne Utsch, in her detailed study entitled Sprachwechsel im Exil. Die 'linguistische Metamorphose' von Klaus Mann [Language Change in Exile. The “Linguistic Metamorphosis” of Klaus Mann], describes a complex range of factors as being responsible for Klaus Mann’s linguistic transformation. His initial motivation for acquiring the English language was, she writes, his pressing need to present talks and published works to the American public to further his anti-fascist political objectives. And while Klaus Mann, up until the outbreak of war in 1939, was predominantly characterised by his self-conception as a representative of the German linguistic and cultural community, his disappointment at the failure of the “other Germany” to materialise as a resistance movement led to the dissociation apparent in his transition from spoken to a written use of English. For Klaus Mann, this shift was the expression of an identity as a world citizen. Upon the conclusion of World War Two in 1945, Mann travelled through Germany as a special correspondent for the US military paper Stars and Stripes but ultimately voiced his disappointment at the experience stating, in summary, “you can’t go home again”.

Sylvia Schütz, Monacensia. Literaturarchiv und Bibliothek München

Further reading:

Naumann, Uwe (Hg.): „Ruhe gibt es nicht, bis zum Schluss“. Klaus Mann (1906-1949). Bilder und Dokumente. Reinbek bei Hamburg: Rowohlt 1999

Utsch, Susanne: Sprachwechsel im Exil. Die „linguistische Metamorphose“ von Klaus Mann. Köln / Weimar / Wien: Böhlau 2007