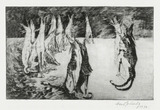

Lea Grundig: Night in the Atlit Camp, watercolour (August 1941)

Lea Grundig: Night in the Atlit Camp, watercolour (August 1941)

Zweitausend Menschen […] versuchten, ihrem Leben durch Tun einen Sinn zu geben. Sie entsannen sich ihrer Berufe, und siehe, sie brauchten sich gegenseitig. […] auch ich fand eine Beschäftigung. Denn es gab keinen, der nicht einmal im Jahr Geburtstag hatte, und da wurden Geburtstagskarten gebraucht mit Bildchen; es mußte vorgezeichnet werden für Stickereien und Muster.

[Two thousand people [...] tried to give their life meaning by doing. They remembered their professions, and, lo and behold, they needed each other. [...] I also found employment. For there was no one who did not have a birthday once a year and there was a demand for birthday cards with little pictures; there was sketching work to be done for embroidery and templates. (ed. trans.)]

From the memoires of Lea Grundig, 1958

The artist Lea Grundig reached Palestine in November 1940 as a survivor of the shipwrecked SS Patria and thus as an illegal immigrant. The British Mandate government interned her in the Atlit detainee camp. After a short time the prisoners began to organize themselves. Everyone needed something and everyone could do something. Lea Grundig could draw and that's precisely what she did there. For example, she designed greeting cards for the community and helped produce the camp newspaper. As an artist she mainly captured scenes of everyday camp life, for example, in the watercolour Night in the Atlit Camp. She created about 100 artistic works during almost a year of internment. Many of these deal critically with fascism, such as the 18-part series Antifaschistische Fibel (Antifascist Primer).

In March 1941, Lea Grundig covered the walls of the camp laundry room with red blankets, attached her drawings to these with pins and opened her first exile exhibition. The works she exhibited were as varied as her “journey” there: “Landscapes and pictures of animals that were created in Bratislava hung there, the Greek islands as seen from the ship, and numerous drawings of the people here. A political committee had also already emerged [...]. [...] by the way, the British camp management had censored and stamped the drawings beforehand.” (Lea Grundig, Gesichte und Geschichte, 1984)