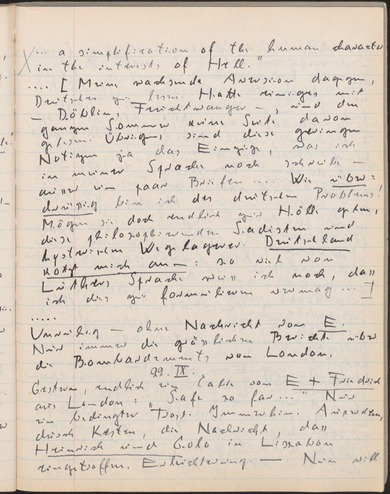

Language

Es sprach zum Mister Goodwill

ein deutscher Emigrant:

"Gewiß, es bleibt dasselbe,

sag ich nun land statt Land,

sag ich für Heimat homeland

und poem für Gedicht.

Gewiß, ich bin sehr happy:

Doch glücklich bin ich nicht."[A German emigrant said

to Mr. Goodwill:

"Certainly, it remains the same,

I say land now instead of "Land",

for "Heimat", I say homeland

and for "Gedicht" I say poem.

There is no doubt, I am very "Glücklich":

but happy I am not." (ed. trans.)]

Mascha Kaléko, Der kleine Unterschied, from her estate

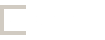

Language is a repository of memories and experiences. It is the bearer of breeding and culture, and the central access to social life and structure. What are the repercussions of being forced to relinquish one’s native language in the blink of an eye and afterward only allowed to speak a foreign one? Through their act of flight into exile members of a linguistic group are expelled and cut off from the living practice of their mother tongue. In addition, they must learn a new language that is foreign for them: the rich connotations that are evoked in each word, their multileveled meanings and the actual currency of vocal expression must be relearned in a foreign language.

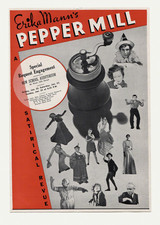

Especially for artists of the written word in exile - authors, film writers and playwrights- conversational exchange is a central experience. Their artistic medium, their mother tongue, becomes problematic as the contact to their native audience is torn away. None the less, many emigrant artists from Germany clung to the German language after 1933. The reading public in exile had to fall back on translations, that when possible tried to iron out the particularities of different languages. Reflections on problems of language became a central theme and can be found in innumerable works of literature and accounts penned by exiles. The belief that his philosophic outlook and the German language are inseparable was noted by the philosopher and composer Theodor W. Adorno upon his repatriation from exile in New York in 1953. He linked his philosophic thinking and his intellectual exchange with his native language.

However, not every form of exile resulted in change or loss of the native tongue. Many artists, after the founding of the GDR and its increasing restrictions, fled to West Germany. They lost their familiarity with a culture and established social networks, but they did not lose their native language. None the less, many saw themselves as exiles.

What role does language play in an age of global immigration? Through global mobility, many countries have witnessed the establishment of communities of immigrants that share a common language. For cultural exchange and daily direct communication, the language of the host country is a necessity. The ability to take part in a language group assures entrance into and participation in a cultural community.

Philosopher Ernst Bloch was himself an emigrant who returned to Leipzig in 1948. In a quote from a lecture in 1939, he stated: “It is not possible to destroy a language, without in that act destroying its culture. On the other hand, it is not possible to preserve and develop a culture without speaking the language in which it is formed and is lived.” (ed. trans.)